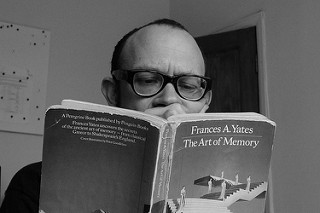

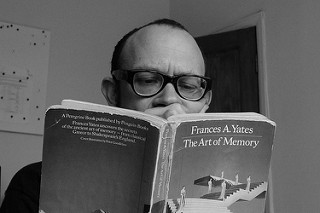

Twenty-two years ago, during one of those impossibly short but paradoxically long 12-week terms at Cambridge, when one is expected to cram a couple of centuries worth of literature into your head and keep it there, it was suggested I might read Frances Yates’ The Art of Memory.

Twenty-two years ago, during one of those impossibly short but paradoxically long 12-week terms at Cambridge, when one is expected to cram a couple of centuries worth of literature into your head and keep it there, it was suggested I might read Frances Yates’ The Art of Memory.

I started it, the book bored me silly, so I read something else. Even had I read it cover-to-cover, I wouldn’t remember a single line, as I don’t remember anything I read at University, either critical or primary texts.

Were I to do it all again, I would join an institution whose sole curriculum consists of having to learn a poem a week (from “the Canon”, if you must), and anything else you might want to dip into around that, with a tutorial based on the recitation of your poem, a cup of tea, and a chat. Your final “exam” would have you reciting as many of the poems you can remember, followed by an audit of your heart and mind in the fullest and least fact-checking sense possible.

Such a University and such a course doesn’t exist, but it should.

Frances and I are back together again. And this time, I’m ready for her, relishing the arcane lore she’s intent on telling me about (no more arcane, as we are both aspiring mnemonists). Or not. For although she whitters on about it, Frances has never utilized the mnemotechnics she writes about.

There is no doubt that this method will work for anyone who is prepared to labour seriously at these mnemonic gymnastics. I have never attempted to do so myself, but…

No walking the talk for Yates (she is an academic, what did you expect?) but still a great primer on art of memory, or memorization if you prefer.

The book was written in 1966, but certain lines ring even more true now than they did in the pre-Google age:

We moderns who have no memories at all may, like the professor, employ from time to time some private mnemotechnic not of vital importance to us in our lives and professions. But in the ancient world, devoid of printing, without paper for note-taking or on which to type lectures, the trained memory was of vital importance. And the ancient memories were trained by an art which reflected the art and architecture of the ancient world, which could depend on the faculties of intense visual memorisation which we have lost.

I have decided to read this book in the next couple of weeks slowly and appreciatively, as this text has suddenly become “of vital importance” when not even five days ago, had you gifted me a copy, I would have passed it on directly to Oxfam.

How skittish and pliable the mind, but perhaps another piece of evidence that everything is waiting for you, particularly the books, people, and experiences you now dread having to spend time with, but might love when you’re ready for them to come into your life.

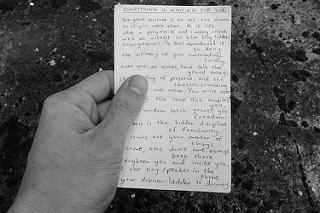

I have been carrying around the poem for the last few days copied neatly onto a 5″ x 3″ Correspondence Card, the card starting to feel intimately used as well as useful, on its way to disintegration through repeated folding.

I have been carrying around the poem for the last few days copied neatly onto a 5″ x 3″ Correspondence Card, the card starting to feel intimately used as well as useful, on its way to disintegration through repeated folding.

Twenty-two years ago, during one of those impossibly short but paradoxically long 12-week terms at Cambridge, when one is expected to cram a couple of centuries worth of literature into your head and keep it there, it was suggested I might read Frances Yates’

Twenty-two years ago, during one of those impossibly short but paradoxically long 12-week terms at Cambridge, when one is expected to cram a couple of centuries worth of literature into your head and keep it there, it was suggested I might read Frances Yates’