On Saturday afternoon I sat in the balmy sunshine of the Southbank listening to poetry and tweeting as the planet continued to heat to the point of expiration.

Damn fine poetry it was too. And no poetry damner and finer than Rhian Edwards.

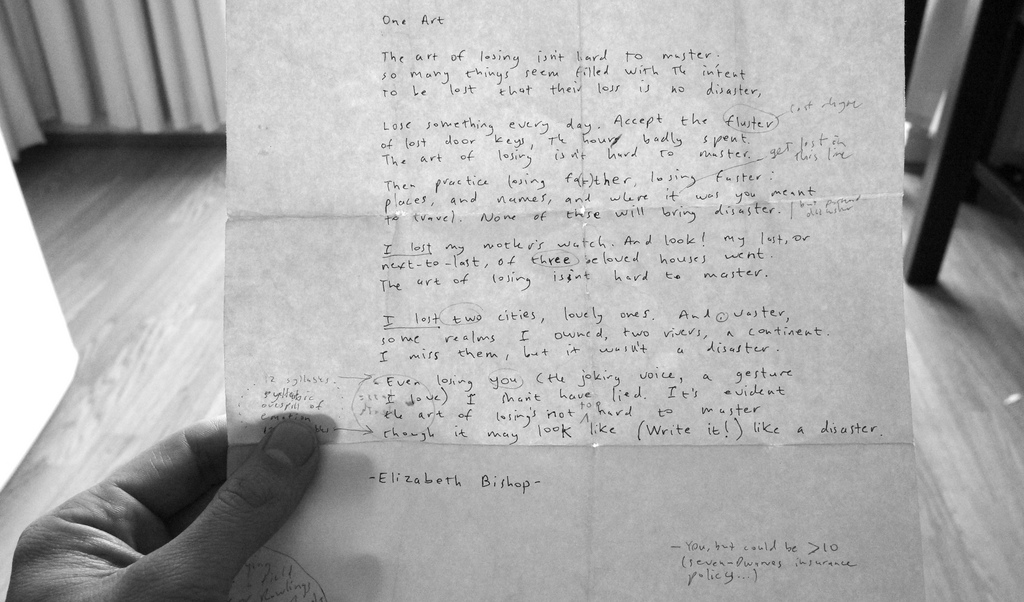

What made Edwards utterly compelling and captivating was that she recited every word of every poem. Not a single word read, and so not a single word retrieved by eye from the page a distant-distancing two feet away before making the 10cm journey into her visual cortex, then pumped out of word-hole to the audience where only then we begin making sense of it all with our auditory wetware.

When you learn a poem by heart, the cells of all your body become marinated with that poem. It seems as if the distance between audience and speaker is reduced too.

When you learn a poem by heart, the cells of all your body become marinated with that poem. It seems as if the distance between audience and speaker is reduced too.

If that poem is “yours”, then you are no doubt becoming even more marinated in yourself, more YOU, in a Whitmanesque, Singing-The-Body electric kind of way. Every lung-sponge, stomach-sac, bowels sweet and clean in service to that poem. Every armpit, breast-bone, jaw-hinge, freckle, heart-valve consorting to make you feel what the poet felt in the writing and now reciting of her thoughts and sentiments.

It’s altogether special, and I can’t really get enough of it, this marinating of my own cells in poetry. Particularly other people’s poems. I am already far too stewed to add self-expressiveness to the mix, but others people’s “stuff”, learnt by heart dovetails in extraordinary ways with to how I feel, think, and sometimes even act. It’s alchemical.

I also get a kick out of witnessing this alchemy in others, as one rarely can these day, unless you’re a Slam Poetry fundie. And even then: do you always want someone’s inner world microphone-slammed into you? (That is not a rhetorical question. The answer is no.)

This year’s theme for National Poetry Day is ‘Stars’, and so rather cleverly (unintentionally cleverly), a bunch of us have decided to gather together under the stars in the not so sweet and not so clean bowels of gothic Abney Park chapel to recite our favourite poems from the last couple of centuries.

This year’s theme for National Poetry Day is ‘Stars’, and so rather cleverly (unintentionally cleverly), a bunch of us have decided to gather together under the stars in the not so sweet and not so clean bowels of gothic Abney Park chapel to recite our favourite poems from the last couple of centuries.

We won’t be reciting work we’ve written (there’s enough of that about), but rather the poems we love, the poems we’ve ingested and set to work within us.

Tickets are £3 and all profits go to one The Reader Organisation‘s Care Leaver Apprenticeship programme.

Do join us: http://byheart.readmesomethingyoulove.com/events/

This piece was written for The National Poetry Day website.